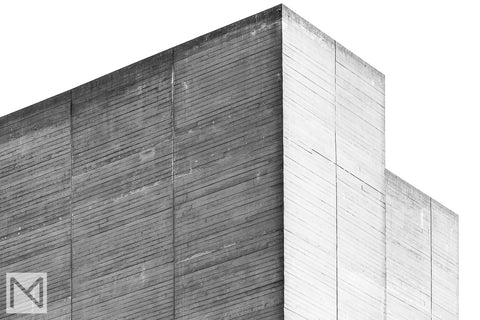

You don't have to travel too far in today's modern western cities to find something made from concrete. It may only be as small as a bollard, or it may be as high as a tower block, but as a building material it's hard to avoid. As bricks, glass, steel, and wood come in and out of fashion, concrete remains as a constant note, humming along in the background as the reinforced core of a skyscraper, or shouting from the rooftops of the most daringly Brutalist buildings.

Made from a combination of aggregate and cement, concrete's ability to allow designers to break free from the constraints of the brick, the girder and the beam has meant it remains a key tool in the architect's arsenal. It has endured for years following its first appearance thousands of years ago, and its gradual renaissance from the 15th century onwards.

Concrete in architecture is probably most strongly associated with the Brutalist movement, which was at its peak in the mid 20th Century. Before that, it was used extensively by the Romans until the secret to its manufacture was lost. The reason many of Rome's famous antiquities such as the Pantheon and the Colosseum are still around today is due to the enduring nature of the concrete from which they were built. Indeed, the dome of the Pantheon remains the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world.

It's not just the durability of concrete that appeals to architects, but its versatility. Unconstrained by the shape of bricks, architects could pour liquid concrete into new and hitherto unseen shapes, expressing themselves in ways previously unheard of. The Modernist movement, with its emphasis on breaking with the past and encouraging new means of expression, be it in painting, sculpture, or architecture, meant new structures were appearing that shouted of the future, with its utopian ideals and grand possibilities. Gone were the gothic arches and neoclassical pillars of the Victorian days. The sinuous curves of Art Nouveau, the symmetrical geometry of Art Deco, and in particular the ground-breaking style of Charles Rennie Mackintosh were all hinting at new directions and eventually we began seeing asymmetrical concert halls, extraordinary churches, tower blocks with pavements in the sky, and fantastical geometric car parks.

Brutalism has not been popular with everyone, particularly modern politicians. Birmingham Central Library, designed by John Madin in 1974 and infamously demolished in 2016, was refused listing by architecture minister Margaret Hodge, who said "I’m not listing [the library] because I’m a democrat. The English don’t like Brutalism." Even buildings with a significant cultural heritage, such as Trinity Square Car Park in Gateshead, famous for being featured in the 1971 Michael Caine film Get Carter, did not escape the demolition ball, and was knocked down in 2010 despite a campaign to save it. Architect Owen Luder bemoaned the change in fortunes of Brutalist architecture: "In the sixties my buildings were awarded, in the seventies they were applauded, in the eighties they were questioned, in the nineties they were ridiculed, and when we get through to 2000 the ones I like most are the ones that have been demolished."

There are still reasons for hope. Many of our best Brutalist structures are listed - not just the famous Barbican estate in London by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, Grade II listed since 2001, but less obvious candidates such as Preston Bus Station, listed in 2013 in recognition of the "ingenuity of the design," according to English Heritage. Not everyone welcomed the decision, least of all then Preston City Council leader Peter Rankin, saying the listing was "not the outcome we were hoping for", citing an estimated £17m cost of modernisation.

The polarisation of Brutalism is no more evident than in the city of Durham, where the Grade I listed Kingsgate Bridge spans the river Wear alongside the endangered Dunelm House, the University of Durham's Student Union building. The University has decided to demolish the latter in favour of a brand new building, the design of which will be open to a competition, claiming it is too expensive to maintain the building in its current form. Despite strong opposition by the 20th Century society and English Heritage, the building was granted a Certificate of Immunity from Listing (COIL) by the Department of Culture, Media and Sport. In a positive recent development, however, the government announced plans to review the decision to grant the COIL and the future of the building remains uncertain.

So what is the future of concrete? Despite the strong opinions that Brutalism invokes, it is still a remarkably popular building material, even causing some people to coin the phrase 'neo-Brutalism' to describe its use in ever more daring modern contexts. Its use in stairwells such as that seen in the Tate Modern's brand new Switch House suggests that it's not going anywhere soon, and its millennia long journey is not about to end.

Buy prints of architecture photography by Nick Miners.